The Unspoken Divide: Colorism, Class, and the Layers Within Black America

- Marcus D. Taylor, MBA

- Jul 22, 2025

- 6 min read

In a time when many in the Black community feel as though we are witnessing a regression in opportunity—especially as DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) programs are being challenged or dismantled—there’s a growing fear that we’re being pushed back into a past we fought so hard to escape. While I personally don’t subscribe to this fabricated fear, I do understand that it feels real to many, especially given the lived experiences that shape those perceptions.

Yet what’s often left out of these national conversations isn’t just about what’s being done to us—but what’s happening within us.

There are struggles inside our community that go largely unaddressed in popular media and mainstream discourse. And two in particular continue to show up—sometimes subtly, sometimes violently—in our families, schools, organizations, and self-image:

Colorism

Class conflict, especially regarding the Black bourgeoisie

School Daze Was More Than a Movie

One of the most influential films of my life is School Daze, directed by the brilliant Spike Lee. This film didn’t just entertain me—it shaped me. Growing up in the Orange Mound community of Memphis, Tennessee—one of America’s oldest Black-founded neighborhoods built from the Deadrick Plantation—School Daze hit home.

My sister and I were among the light-skinned kids in our neighborhood. I have hazel eyes and was always well-mannered—because my mother demanded nothing less. But that appearance created friction. I got into fights. I was told I thought I was better than others. I was accused of being weak or soft. Why? Because of my complexion and how I spoke.

And yet, I admired the darker boys. I thought they were cooler. I even wished my skin was darker and my eyes were "normal." But society—both inside and outside the Black community—had already created categories I never agreed to.

According to Dr. Margaret Hunter (2007), these perceptions are part of what she calls “color capital”—the privileges and penalties associated with skin tone within the same racial group. While lighter-skinned individuals may gain certain social or economic advantages, they are often alienated by their peers and accused of disloyalty.

Colorism: A Legacy of Pain

Colorism—coined by author Alice Walker in 1982—is more than just a preference. It’s a reflection of colonial and slave-era ideologies that equated lighter skin with proximity to whiteness and thus with value, beauty, and intelligence. This internalized belief system continues to shape our institutions, relationships, and even our self-worth.

Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum (1997) refers to this as internalized racism—the silent inheritance of societal values that place whiteness as the standard. In a 2009 study, Hamilton, Goldsmith, and Darity found that lighter-skinned Black women were significantly more likely to be married than their darker-skinned counterparts, even when controlling for education and income.

We see it in dating, hiring, and media representation. We see it in families—when one child is called "pretty for a dark-skinned girl" or another is labeled “high yellow.” And we’ve seen it in pop culture for decades.

The Divide of Class: The Boogies and the Forgotten

Beyond skin tone lies another, often sharper, blade: classism. More specifically, the longstanding mistrust between what’s often called the “Black bourgeoisie” (or “boogie class”) and the working-class or Southern-rooted Black population.

The Black middle and upper class—those with degrees, titles, and mortgages—have often been accused of trying to “act white.” In his seminal work Black Bourgeoisie, sociologist E. Franklin Frazier (1957) described this class as aspiring to cultural assimilation, often reinforcing distance from working-class Black communities as a way to gain credibility in white spaces.

This perception—true in some cases, false in others—has created a trust gap. Those on the lower rungs may see upwardly mobile Black people as “sellouts,” while professionals feel misunderstood or blamed for systemic issues they didn’t create.

Dr. Mary Pattillo (1999) notes that the Black middle class often walks a fine line: expected to uplift the race, yet often isolated from the people they’re supposed to represent. It’s a tension that still plays out today—between the boardroom and the barbershop, the HBCU and the block.

A Sowell Perspective: Culture and Class from the Inside Out

Economist Thomas Sowell, in his book Black Rednecks and White Liberals (2005), takes this conversation even further. Sowell argues that many cultural behaviors often associated with the Black underclass—such as anti-intellectualism, bravado, and mistrust of education—were not inherited from Africa but from the white “cracker” culture of the American South.

“What the rednecks and crackers brought with them, which would have a lasting effect on the Black community, was a cultural attitude that valued impulsiveness over planning, flamboyance over substance, and pride over humility.” (Sowell, 2005, p. 27)

Sowell asserts that Northern Blacks who distanced themselves from these traits were seen as “boogie” or disconnected—not because they were trying to be white, but because they were trying to rise above a dysfunctional cultural inheritance. Whether one agrees with all of Sowell’s views or not, his work illuminates the complexity of our internal divides: they’re not just about money—they’re about learned behavior and cultural association.

HBCUs: Mirrors of Our Struggles and Our Power

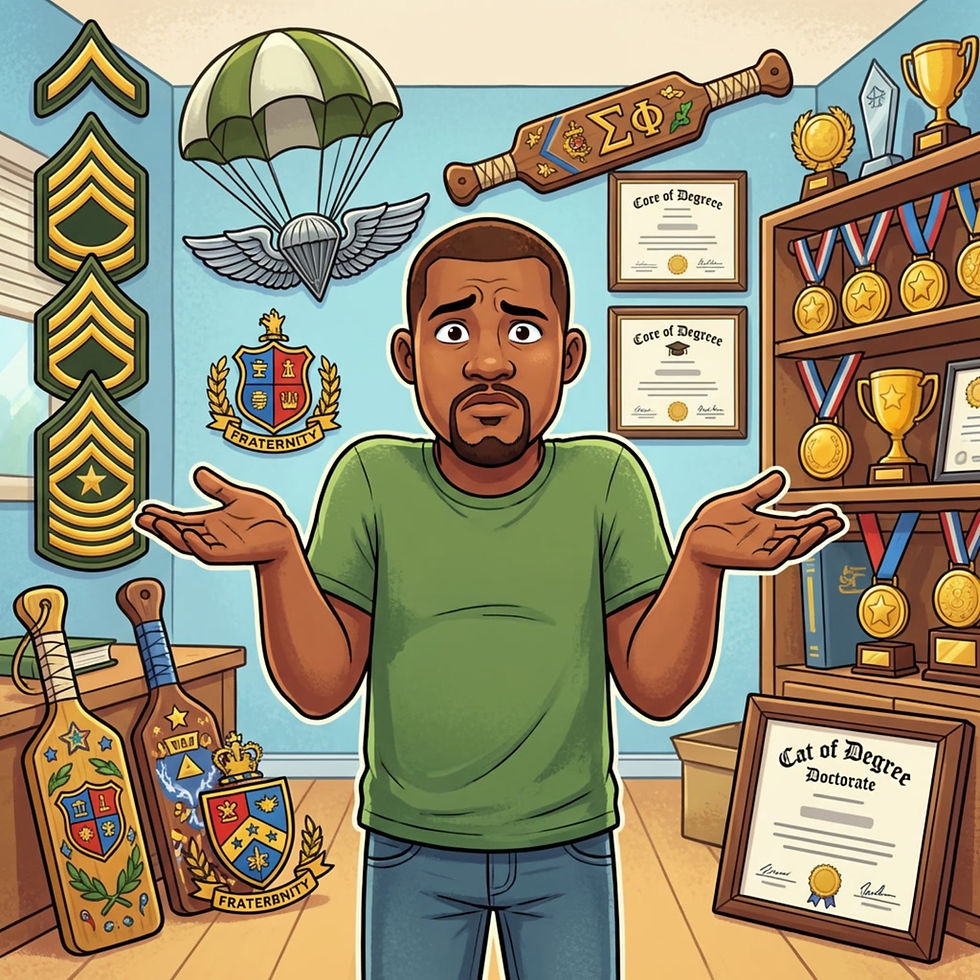

When I entered Texas Southern University in 1998, I witnessed many of the dynamics portrayed in School Daze firsthand. The rivalries between Omega Psi Phi (Ques), Kappa Alpha Psi, and Sigma Rhomeo weren’t just about letters—they were about image, class, and philosophy. Each had its own identity, tradition, and social standing. The sororities—Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha—were equally competitive and culturally rich.

Sigma Rhomeo, the fraternal order I joined, was unapologetically different. With less rigid structure but strong influence, it showed that power doesn’t always come from the system—it can also come from authenticity. And that’s the lesson I carried with me: we can disagree without division if we commit to mutual respect.

But even during the filming of School Daze, an incident occurred that exposed just how deep internal biases ran. The actor cast to portray the university president was reportedly considered “too dark,” even though the actual university president at the time was a lighter-skinned man. As a result, the crew was asked to leave Morehouse College during filming. That moment wasn’t just a behind-the-scenes anecdote—it was a stark reflection of how colorism can operate even within institutions created to uplift Black excellence.

The Media’s Role in Keeping Us Divided

Media and music have both challenged and reinforced these divides. We cheer for the underdog in stories of survival, but often mock the educated for “talking proper.” We praise Black excellence but scrutinize how it’s achieved. We hear lyrics that glamorize struggle, but rarely hear messages that honor strategic thinking or academic success.

When New Jack City dropped and Nino Brown, played by Wesley Snipes, stabbed the light-skinned character Kareem and sneered, “I never liked you anyway, pretty mother—”, the crowd in many theaters erupted. Why? Because that moment didn’t just feel cinematic—it felt personal. It mirrored real-life tensions that many had lived through.

That line cut deeper than the script. It captured decades of silent resentment, internal bias, and pain tied to complexion, masculinity, and perceived privilege—all wrapped into a few seconds of raw, cultural expression.

The Path Forward: Healing Begins with Truth

These internal divides—colorism, classism, cultural fragmentation—are the result of historical manipulation, systemic design, and generations of misunderstanding. But they’re not unbreakable.

Here’s what we must commit to:

Name the issues.

Stop pretending these divides don’t exist. Bring them into the light.

Educate and unlearn.

Teach our young people that Blackness isn’t a monolith—and success doesn’t equal selling out.

Reject false binaries.

You can be “woke” and still respect tradition. You can be “boogie” and still care about the hood. You can be Southern and sophisticated. These aren’t opposites—they’re part of the same rich tapestry.

Amplify full-spectrum Blackness.

Media must portray us in all our depth—from janitors to judges, from spoken word to stockholders.

Conclusion: A Call to Reconcile and Rebuild

My story isn’t unique—but it is mine. And I share it not to elevate my journey, but to validate others who’ve walked similar paths. The hardest part of building community isn’t finding a cause—it’s overcoming the walls we’ve built between each other.

We don’t have to agree on everything. But we do need to stop mistaking diversity for division.

Because if we don’t address what’s happening within, we’ll never be strong enough to handle what’s coming from without.

References (APA 7th Edition)

Frazier, E. F. (1957). Black bourgeoisie: The rise of a new middle class in the United States. Free Press.

Hamilton, D., Goldsmith, A., & Darity, W. (2009). Shedding “light” on marriage: The influence of skin shade on marriage for Black females. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 72(1), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2009.05.019

Hunter, M. L. (2007). The persistent problem of colorism: Skin tone, status, and inequality. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00006.x

Mitchell, K. (2014). Living with Lynching: African American Lynching Plays, Performance, and Citizenship, 1890–1930. University of Illinois Press.

Monk, E. P. (2014). Skin tone stratification among Black Americans, 2001. Social Forces, 92(4), 1313–1337. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou007

Pattillo, M. (1999). Black picket fences: Privilege and peril among the Black middle class. University of Chicago Press.

Sowell, T. (2005). Black rednecks and white liberals. Encounter Books.

Stephens, D. P., & Few, A. L. (2007). The effects of images of African American women in hip hop on early adolescents' attitudes toward relationships. Sex Roles, 56(3–4), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9141-6

Tatum, B. D. (1997). Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria? And other conversations about race. Basic Books.

Wilder, J. (2010). Revisiting “color names and color notions”: A contemporary examination of the language and attitudes of skin color among young Black women. Journal of Black Studies, 41(1), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934708325543

Comments