“If You Don’t Like It, Leave.” Why That Phrase Often Seems Honest but Undermines Leadership

- Marcus D. Taylor, MBA

- Dec 22, 2025

- 5 min read

Why That Phrase Often Seems Honest but Undermines Leadership

I have heard the phrase.

I have believed the phrase.

I have probably said the phrase.

“If you don’t like it, leave.”

When it aligns with your vision, your culture, and your observations, it often seems rooted in truth. It sounds direct. It sounds clear. It sounds like accountability instead of compromise. In certain moments, it even seems necessary.

But after watching people, systems, and organizations operate across time, it often seems that this phrase does more harm than good. Not because boundaries are wrong. Not because standards are unnecessary. But the phrase is frequently used in place of leadership rather than as a result of it.

The Difference Between Perspective and Comfort

When leaders say, “If you don’t like it, leave,” it often seems less about protecting the mission and more about protecting comfort. The statement does not invite explanation. It does not ask for a contribution. It does not seek understanding. It closes the conversation.

The unspoken message becomes simple.

Agreement equals belonging.

Disagreement equals disqualification.

That framing creates environments where questioning is treated as a threat rather than engagement. Where alternative ideas are dismissed instead of examined. Where discomfort is avoided rather than understood.

Leadership does not require agreement.

Leadership requires discernment.

Why Discomfort Often Seems Misinterpreted

There is a consistent pattern across organizations. When someone introduces a thought that challenges culture, tradition, or long-standing practices, the response is rarely curiosity. More often, it becomes, “Why are you here if you do not like how we do things?”

That response may sound reasonable, but it often seems rooted in entitlement. It assumes the organization has already reached its best form and that any challenge to it must come from someone who does not belong.

That is where organizations stall.

Progress does not come from silence. It comes from leaders who can say:

“I am not used to hearing this.”

“I do not agree with this yet.”

“I am uncomfortable with this idea.”

“Let me listen anyway.”

That posture does not weaken leadership. It strengthens credibility.

The Political Parallel and Why It Matters

This language appears far beyond organizations. When individuals raise concerns about systems, policies, or governance, the response is often, “If you do not like it here, then leave.”

It often seems like loyalty. In practice, it communicates exclusion.

No one ever says, “If you agree with me, you should leave.” The agreement grants acceptance. Disagreement triggers dismissal. That creates a hierarchy where one group is positioned as morally correct and therefore entitled to decide who belongs.

Strong systems do not operate this way. Fragile ones do.

Why House Rules and Organizational Rules Are Not the Same

There is an important distinction that often gets overlooked.

In a household, parents carry full responsibility. Rules exist because accountability is centralized. When adult children reject those rules, it is reasonable for them to create their own space.

That is ownership.

Organizations are different.

No single person owns the mission. Leadership exists to steward it. Stakeholders, members, and contributors all have a legitimate voice. Titles do not grant supremacy. They grant obligation.

Leaders serve the organization. They do not replace it with themselves.

When leaders behave as though the organization belongs to them personally, culture becomes dependent on personality rather than principle. That is when instability begins.

Standards Versus Arrogance

There is a correct idea hidden inside what people are often trying to say.

The issue is not preference. The issue is standards.

If a role has clear expectations and someone refuses to meet them, that is not exclusion. That is alignment. If a job requires greeting customers within a defined time frame and someone refuses because of personal belief, the issue is not superiority. The issue is fit.

Standards are impersonal.

They are documented.

They apply regardless of who is in charge.

They outlast individual leaders.

Arrogance is different. It is personal. It shifts with ego, mood, and insecurity. When expectations exist only in a leader’s mind, organizations become unstable. When dissent is treated as disrespect, trust erodes.

Why Personal Preferences Damage Organizations

One of the clearest signs of weak leadership is when personal irritation becomes organizational policy.

If expectations exist only because a leader dislikes something, the organization becomes hostage to temperament. When that leader leaves, the rules change again.

Strong organizations do not operate this way.

They are guided by mission, shared standards, and collective accountability. Leadership transitions do not disrupt identity because identity was never tied to one person.

Listening Does Not Mean Agreeing

Listening does not require concession.

It requires discipline.

It requires the ability to hear an idea fully without immediately neutralizing it. It requires separating intent from impact. It requires recognizing that discomfort is often information rather than danger.

When leaders silence dissent instead of examining it, they trade short-term comfort for long-term decline.

Practical Recommendations for Leaders Who Feel the Urge to Say “If You Don’t Like It, Leave”

Leaders reach for this phrase when fatigue sets in, resistance feels constant, or progress seems slow. The issue is not that leaders experience these moments. The issue is how they respond.

1. Separate Standards From Sentiment

Ask a direct question before responding.

Is this about a documented standard, or is this about personal tolerance?

If it is tied to mission, role, responsibility, or performance expectations, address it as alignment and accountability. If it is not, resist the temptation to turn preference into policy.

2. Replace Exit Language With Clarification Language

Avoid exclusionary phrasing. Use language that seeks understanding.

“Help me understand what you are seeing.”

“Walk me through your reasoning.”

“What outcome are you trying to improve?”

These responses reinforce authority rather than weaken it.

3. Acknowledge Discomfort Without Using It as a Weapon

Leaders can say:

“This is uncomfortable.”

“I am not used to this perspective.”

“I do not agree yet.”

What matters is what follows. Discomfort should inform reflection, not justify shutdown.

4. Anchor Decisions in Mission, Not Ego

When declining an idea, explain why in mission-based terms.

“This does not align with our priorities.”

“This conflicts with our stated objectives.”

That approach preserves dignity and trust.

5. Treat Transition as Alignment, Not Punishment

When it becomes clear that someone cannot operate within organizational standards, frame transitions around fit rather than failure. Alignment protects both the individual and the organization.

A Better Way to Say It

Instead of “If you don’t like it, leave,” leadership should sound like this:

“If the standards of this organization are not something you can meet, adapt to, or contribute to constructively, it may be best to find an environment that aligns better with your strengths and values.”

That language does not elevate ego.

It protects the mission.

It respects people.

It preserves dignity.

What Leadership Actually Requires

Leadership is not deciding who belongs based on agreement.

Leadership is building systems strong enough to withstand disagreement.

Organizations do not fail because people ask questions. They fail because leaders refuse to hear them.

“If you don’t like it, leave” often seems like a straightforward response.

Honesty without responsibility is not leadership.

Leadership listens, evaluates against standards, and acts in the service of something larger than personal comfort.

That is how organizations endure.

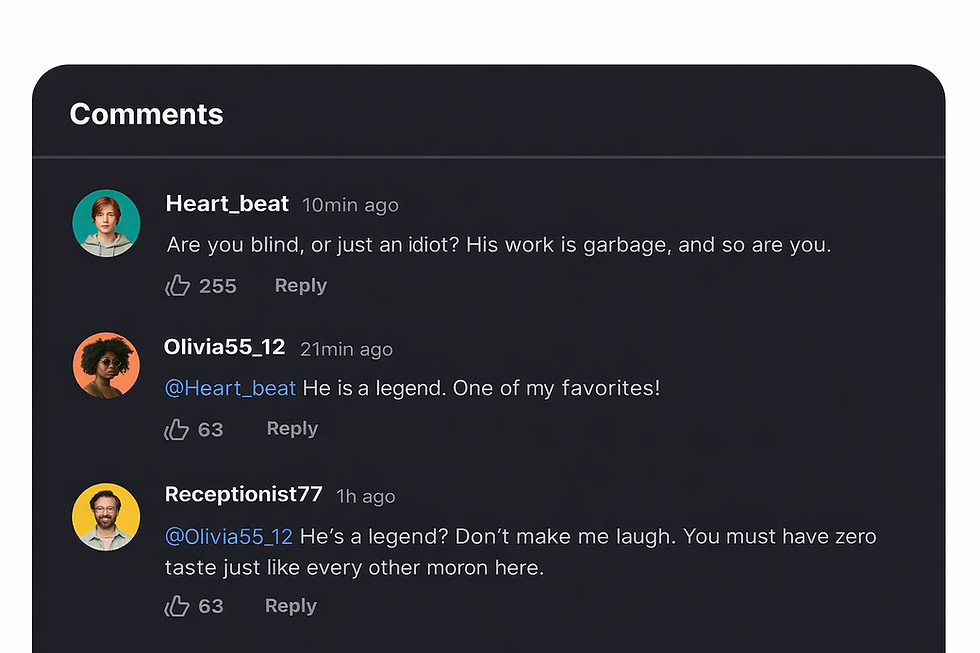

I see this phrase everywhere online, too. It undermines everything good in this world: empathy, perspective taking, openness. The Foss sisters are two communication scholars who have written extensively about “constructive dialogue,” which is a practice that echoes many of the good strategies you’ve recommended here. One of their key tenants is that we should REALLY be open to having our hearts/minds changed when we enter a debate, otherwise it’s all about ego. I think they could use a bit more analysis of power structures that may influence his people enter into debates (not everyone enters on equal footing), but that aside, I bring them up because it reminds me of the authentic position of integrity you’re recommending here for…